Eminem – In Philip Dick’s science fiction novel “The Divine Invasion” from 1981, the protagonist works for a space industrialist and lives alone on a distant, inhabitable planet. To cope with his isolation, he repeatedly listens to the worn-out collection of tapes of a famous female singer’s music, played in a spacey manner. Her enchanting, captivating voice and complex songs keep him emotionally balanced. He’s not just infatuated with her – he’s even more than that, he’s addicted to her, and at times he becomes anxious like a lunatic when he thinks he’s lost the tapes. Once he completes his obligatory tasks, he blacks out his sealed pod, lies down, plays a tape, closes his eyes, and drifts into his magical universe because her mystical presence fills the room. It’s not just her music but her existence itself that provides him refuge, a complex, respected, and splendidly successful life that blurs his seriousness and monotony.

He doesn’t know that he’s not real. In the superior in-studio production – and in our now integrated AI world – not only his sound but his entire existence has been crafted. Their history, career, beauty, and every minute of experience that collectively molds a life, is synthetic. He is designed to satisfy a massive and internal consumer demand with efficiency and skill, and he does so completely. I’ve always thought that Eminem is somewhat similar. I know he exists, but as they say, if he didn’t, we would have to invent him. And to some extent, we have. That individual can be real, but he’s Eminem, who is somewhat illegal, somewhat the catalyst of a record industry, a deity of high-rise paper, crafted with the help of countless hands. And what young person, especially a teenager, has never felt connected in some mysterious way to a detached voice in an alien, loveless void on another planet? A voice that miraculously understands, comforts, and soothes.

“Eminem: The Provocative Icon Who Reshaped Pop Music and Cultural Norms”

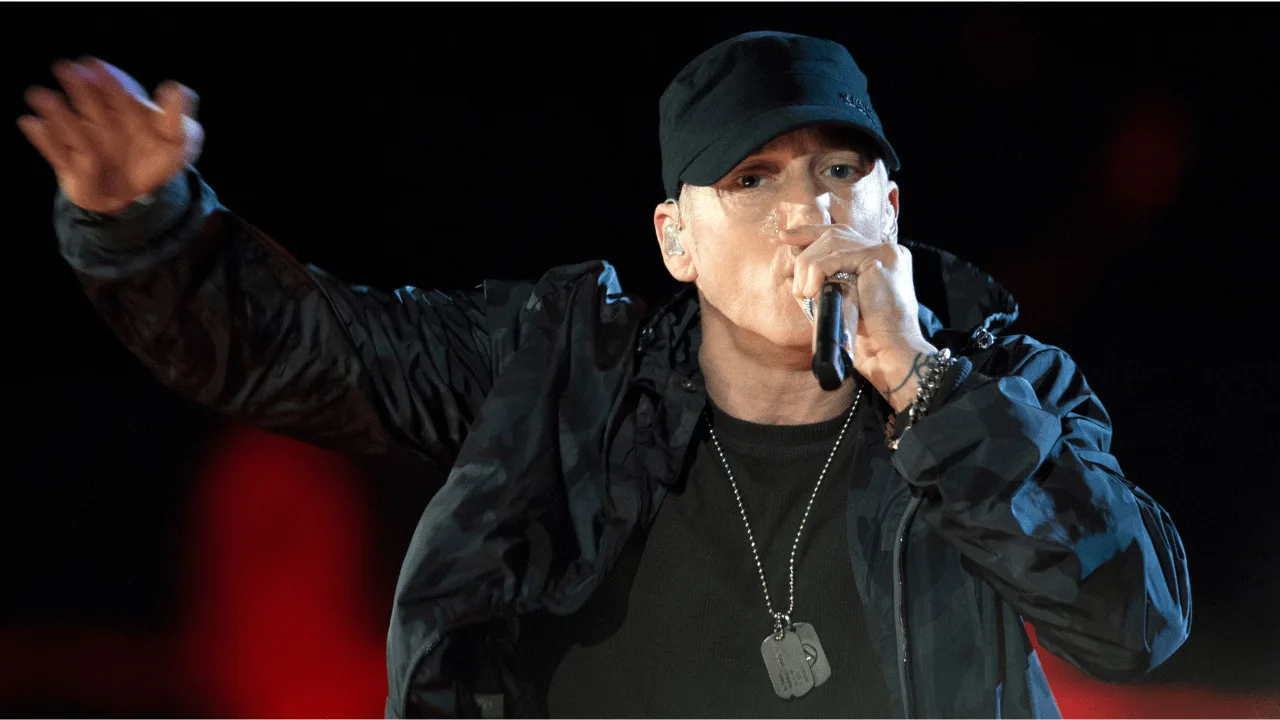

All successful pop music is the creation of a few individuals who craft it, and millions of people who gravitate towards it, shaping it according to their unique desires. And collectively, we needed Eminem to dispel the sluggishness of our own music and stir the calm waters of contemporary pop culture’s stagnant pond. Most of it is produced on a grand scale to align with corporate agendas. But the savior came with a devil’s demeanor, with a mesmerizing charm that defies conventions. Leaving aside the few who know him personally, the rest of us know him only as a projection, as we hear in his provocative and violent lyrics, or as we see him in his videos assuming various personas. We see him slouched in his seat at the MTV Awards, strangely somber, tired, and anxious, or on stage, moving swiftly and provocatively, thrusting a knife at ghosts and cursing them.

We have a collage image of him from photography: his round face looking nun-like when he wears a bandana on his forehead and drapes a sweatshirt hood over it; his toned, tattooed body appearing dangerous and fragile, untimely and already worn out. We feel like we know him through all this and his unbelievably explicit music, where his private life is preserved like a keepsake in a tourist shop. Despite being the world’s biggest pop star, or perhaps because of it, he makes us feel like he’s our neighbor.

“Unveiling Eminem’s Inspiring Journey: From Turbulent Beginnings to Iconic Eminence”

Following all the rules of statistical probability, we should never have heard of Marshall Bruce Mathers III. His parents were musicians, in short, sufficiently talented to present other people’s songs in hotel lobbies in the American Midwest. Ironically, their band was named Daddy Warbucks, after the character from the musical “Annie,” who takes in an orphan and cares for her. In his early years, Marshall must have wished for this benevolence. He married when Debbie was 15 and her husband, whose name is not commonly known, or at least not spoken, was 22. Within two years, Marshall was born, and shortly after that, they split. Marshall’s father, whom he never knew, moved to California. As a child, Marshall tried to contact him, but his letters were returned unread. When Marshall transformed from a trailer-park millionaire with a white-trash Cristal chalice to the platinum-selling rap star Eminem, his father made attempts to reconnect.Eminem rejected this, saying, “F**k him. Leave him.” As a child, he and his mother, Debbie, and his younger brother, lived between Kansas, Missouri (where he was born), and Detroit, ending up in the poor East Side. At the age of eleven, he and his mom were the only white family in a mostly black neighborhood, which later served as the spiritual and factual backdrop for the film “8 Mile.” Eminem has said that when he was younger, race wasn’t a big issue, but as he became a teenager and participated in freestyle rap competitions towards the end of his adolescence, he was singled out as the lone white contestant on the mic, and this led him to being surrounded and defended by his black friends, a loyalty he’s continuously reciprocated, most importantly in protecting his group D12 and The Dirty Dozen. Life as a teenager was hard for him, his unstable mother made it even more difficult, as he’s famously said, she drank and abused prescription drugs, which didn’t work, but she would go through the motions of filing trivial lawsuits for compensation. Imagine, mothers usually disapprove of their kids, but in his case, she went further and kicked him out. He failed the ninth grade three times and dropped out. He was 17, an age when others were graduating.

He took up odd jobs that paid minimum wages and his existence, as defined by statistical probability, was almost non-existent. Throughout, he clung to his dream of becoming a rapper, fueled by his burning, seemingly impossible passion. Eventually, he moved out of his mother’s home, started living with his high school sweetheart Kim, whom he eventually married (and later divorced), and with whom he has a daughter, Hailie. In 1996, he released a self-produced independent CD called “Infinite.” This was his shot at brass rings, but it was average and quickly became a failure. He was 24. The last time I heard Eminem before listening to his most recent single, his disjointed voice was echoing from the intercom speakers of a supermarket outside of Chiusi, Italy. It was his song “Lose Yourself” from “8 Mile,” where the sound of his gunshots spread through the parking lot. I’ve shopped there dozens of times and I’ve always paid attention to the canned music, but I’ve never paid attention to its source. But Eminem gets you. His voice carries a hardness and urgency that’s both unsettling and exhilarating, like gnashing yourself.

He masticates language in his mouth and spits it out in rhythmic torrents, like a crazy drunkard tasting the fiery liquor he can’t control. It’s cliche to say an artist exploded, but in Eminem’s case it’s fitting not just to describe the transformation of a broken, discontented, white-rap-van-driving aspiring superstar into Earth’s biggest music star, but also to describe the way he tore through soft like tissue paper. The flesh of America’s complacent self-image. In 1997, after placing second in a rap olympics held in Los Angeles, his demo tape, The Slim Shady EP, made its way to the early rap super-producer Dr. Dre, who signed him. A year later, before releasing his major label debut, the Dr. Dre-produced Slim Shady LP, he worked on several Dre projects. Selling over four million copies, it became the best-selling rap record at the time. Eminem’s tracks were also, according to rap’s well-worn standards, misogynistic, violent, and homophobic. What’s surprising is that they weren’t racist, perhaps because he saw himself as a black man, someone whom white people wouldn’t have a problem with. But he filled that void with his first hip-hop fantasy: he sings gleefully about raping his mom on “Kill You.”

Just like Eminem’s invention wasn’t enough to escape the harsh reality of his life, Marshall Mathers’ newfound arrogance gave birth to a transformative ego, Slim Shady, his genuine dark side. Eminem pondered about it in the restroom, quite appropriately, and reasoned that it was his fictional alter ego, Shady, who hated homosexuals, wanted to drug and assault a young girl, and even verbally encouraged an adulterous wife and her lover to be killed by her promiscuous husband. For hesitating about this, Dre slapped him.

This record angered both the extreme conservatives and liberals, where there was at least some semblance of agreement. LGBT activist groups and church groups called for his music to be removed from stores and banned from airplay, and he wasn’t given permission to perform at the Grammy or MTV awards. The outcome of this turmoil was as predicted: increased CD sales and a rapid expansion of his fame. His follow-up release, “The Marshall Mathers LP,” sold over 18 million copies worldwide and was nominated for the Grammy’s Record of the Year. It didn’t win – a slightly less controversial Steely Dan did – but Eminem won Best Solo Rap Performance and Best Rap Album, and in an effort to reduce his homophobic image, he performed his hit “Stan” with Elton John at the awards show.

“Eminem’s Defiant Artistry: Challenging Norms and Owning Authenticity”

A powerful gesture to challenge the fever of political correctness. In 2003, he won an Oscar for “Best Original Song” for “Lose Yourself” from “8 Mile,” a movie where – disregarding all controversies – he portrayed himself in a semi-autobiographical role, another layer of self-identity beneath the imposing monolith, fanning the flames of impotence, and his song earned more than $100 million in the U.S., an unprecedented success for an actor-led music film. Eminem’s 2002 release further ignited the smoldering fire of frustration under the monolith of impotence, turning Eminem into a firestorm fueled by impotence. The album covered his turbulent year with remarkable authenticity, a year in which he was arrested twice on gun and assault charges (he received probation), his mother filed a lawsuit ($1,600 was settled), and he divorced his wife. It’s an outstanding record and a chronicle of the car crash that was his life back then. In one track, he murders his wife, and his daughter helps him bury the body. His real daughter, Hailie, contributes her part on the track. On a day when he unexpectedly takes his daughter to work, Eminem invites her to the studio and tells her mom that he’s taking her to Chuck E. Cheese’s.

“Eminem’s Unconventional Journey: Defying Rap’s Typical Trajectory”

Typically, the careers of rap stars are like a magnified firework show that suddenly dazzles but tends to burn out relatively quickly. I think this happens because a) some are love songs and b) the majority of rap somehow embodies revolutions, which either win or lose, they don’t usually endure. Rappers emerge like they’ve been shot from one of their own police-busting fantasies. Sadly, they often end up becoming fashion designers. Eminem is a mischievous, erratic monk who wrestles both real and imaginary demons at once. We can’t see the struggle, but we can see its aftermath, much like waking up from a bad dream. He’s admitted early on that he can’t rap forever, and he’s said that he eventually wants to become an impresario like Dre. He’s hinted at being ready for acting again.There’s no indication he’s interested in starting a clothing line. It also seems like he’s moving forward in some way. At the very least, he doesn’t show any sign of softening: as soon as he released his fourth album, he was already in a showdown with Michael Jackson, depicted as a spastic pedophile in the album’s first single and video, “Just Lose It.” He’s also been depicted in an unflattering light with President Bush in a political battle in another video, which the Republicans don’t want to air. Or maybe he’s trapped in his nightmares, still tossing in his sleep, caught up in an improbable battle against dark forces for his soul that propels him forward while we watch, uneasy.